Context

When Christianity took over Spain in 1492 with the conquest of Granada, knights were no longer warriors but had converted into territorial governors. These rulers affirmed their control by bragging about their heraldic inheritance and services to the crown. Infatuation with the heroic past replaced the contemporary flat reality in the Peninsula, although The New World became the next goal.

Cervantes borrows notions from contemporary Renaissance philosophy to distinguish between what is truth for Quixote and for the rest of the characters. The Renaisssnce philosopher, Montaigne, whose Essais appeared in 1580, is a witness to the blossoming of subjectivity seen in Cervantes´ knight. Montaigne´s Essais were translated into English and known to Shakespeare who quoted a passage from them in The Tempest Act II, Scene I. They were translated into Spanish, probably at the request of Quevedo, a contemporary of Cervantes, who refers to them. They were not printed in Spain due to the Inquisition's index of Montaigne's Essais.

Montaigne also revived the ancient Greek sceptical tradition which he summed up in his personal motto: "Que sais-je?"(What do I know?). The author was searching for an alternative thought process to that of the dogmatic Middle Ages. He condensed his method of investigation in the quote:

"There is more work in interpreting interpretations than in interpreting things ..."

Don Quixote finds truth in his subjective inner experience; other characters find it in the communal truth of external reality. Both Cervantes and Montaigne invited readers to see introspection and individualism as a way of life and the conflict between rationality and belief as a factor of modernity. The intrigue of Cervates´ book is precisely the ambiguity between fiction and reality. Its lasting interest lies in its interpretation of what is true.

Narration

Narrative

In the Prologue to Book 1 Cervantes confides to a friend that his book does not have enough references to be taken seriously. His friend replies with a long list of quotes and says that the author just mention them and the friend will provide the annotations. With the preface by the author citing sonnets and letters from VIPs Cervantes imitates the chivalric novels and suggests that his readers interpret his book as their parody.

Cervantes wrote in his Don Quixote about how the imaginary heroics of the romance novels were presented as realities in Spanish culture. Books which contained legends of chivalry purported to be historical and disguised their fiction in as much realism as possible.

Don Quixote recalls the chivalric tradition and anticipates the modern novel. The romances of chivalry told tales of heroic knights and their adventures to gain the women they loved. Cervantes mimics this tradition and exaggerates it through satire. He shows how distorted their reality is by overstating the protagonist's deeds. On the other hand the narrative points towards the modern novel through its subplots, low and high styles and self-commentary. However, because of its chosen theme it remains unrealistic and realism will be the mark of the new art form of the novel.

Plot

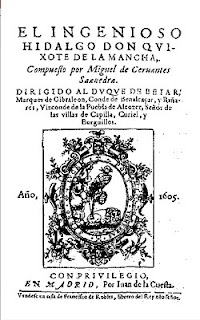

Don Quixote was published in two volumes in 1605 and 1616.

Book 1

Alonso Quixano lives in a village in La Mancha. He respects the ruling classes whom he thinks are his superiors but is compassionate with his peers and inferiors. He is not ambitious for riches and accepts his own noble poverty. He loves his books and through them gradually becomes obsessed with tales of chivalry. He sells his land to purchase more and more books on chivalry which he reads addictively.

Finally he decides to turn himself into a knight like that of his books and sets out to enact his dreamworld. He chooses Dulcinea, a farm girl, as his lady. His first adventure is to confront some travelling salesmen who do not recognise Dulcinea's beauty and ends up badly beaten. Some acquaintances make a bonfire with all his books in order to persuade him to stop his new quest.

On his second adventure which lasts 3 weeks Sancho accompanies Quixote. This is comprised of a series of comedies of errors such as mistaking windmills for giants and an inn for a castle or bedding down with a housemaid who mistakes the room. More misguided events occur with the innkeeper, the locals and a religious procession.

Mixed with the adventures there are narratives and morality stories following the costumbrista tradition. Two long discourses also form part of Book 1: one is a golden age myth recounted to a group of goatherds; the other is a debate on the superiority of letters to arms.

Book 2

In this tale of irrealities suddenly reality interrupts the author while he is writing chapter 59. He finds out that another writer, Avellaneda, had published a pirate version of Book 2 containing new adventures of Don Quixote. Cervantes incorporates this episode into the second volume by having Sancho and the knight hear about the other version. They go straight to Barcelona and kidnap a character from the pirate narrative. In line with the basic message of the book: fiction informs reality.

This volume introduces another character, Carrasco, who tries to bring Don Quixote back to reality. When they travel to Tobosa to visit Dulcinea they meet 3 peasant girls. They try to deceive Quixote into accepting one as Dulcinea. However, the knight refuses to be deceived, believing that some enchanters have turned Dulcinea into an ugly peasant girl. Then Don Quixote wins a battle against a knight who is Carrasco in disguise. Encouraged by this the hero wants to engage battle with a lion.

A Duke and Duchess play a series of tricks on Quixote injuring him and his squire. Sancho is appointed governor of an island in another joke but he shows loyalty to his knight by abandoning his governorship to remain with Quixote.

Carrasco disguises himself as The Knight of the White Moon and challenges Quixote to battle on the condition that if he loses he will abandon knight errantry completely. Carrasco wins and Quixote must abandon his dream.

After more practical jokes played by the Duke and Duchess the pair return home to La Mancha. On arriving Quixote sleeps for a long time and on awakening recognises that he is Alonso Quixano. After renouncing chivalry he dies.

Structure

Don Quixote is structured in three parts:

The first section corresponds to the knight's first expedition. This is a parody of a romance tale. The narrator is Cervantes using a direct narrative style.

The second part is what remains of Book 1 and is presented as historical with daily reports on events. Here Cervantes is acting as supposed presenter of a manuscript by Cide Hamete Benengeli. He frames the supposed Benengeli narrative by interrupting it to comment on discrepancies in the 'original' script thus underlining that the pretence that the story is historical. Cervantes is taking a step back from his own fiction to reflect on fiction itself. The composer has become editor.

The third part is Book 2 which is composed as a traditional novel including themes and character development. Here Cervantes inserts himself as a character in the novel. The characters, who become aware of the pirated version about them, try to change the next editions. It is thus difficult to distinguish original and pirate plots, reality becomes fiction. The question is so complicated that readers are forced to trust Cervantes. The reader is thus drawn into the story and the problem of the sanity of its protagonist. What is fictional and what not? Readers are forced to reflect on the very idea of narration and its relationship to reality just as Don Quijote is also compelled to question chivarly at the end of the novel. The form of the book reflects its function of creating a parallel reality to entertain and instruct readers and encourage us to re-examine our preconceived ideas. Don Quijote thus appears as a mirror world which refects the mix of reality and fiction. It is a 17th. century Metaverse.

Narrator

In the first novels written in English, such as Defoe's Moll Flanders, the narrator establishes a point of view which can be first person or omniscent. The storyteller then invents his characters and events to suit his purpose trying to be as verosimil as possible so as to be believed by the reader. Cervantes chose to approach this pretended realism by inventing a manuscript and its Moorish author as historical realities. To maintain the appearance of historicism Cervantes documents Quixote's adventures. He writes the fictional translation in the second part of Book 1 as if it were a journal.

In the first section of the book the protagonist is chronicled as a reader who has been possessed by the romace fictions he has read. However, in the second section Cervantes takes one step back from his character who has now become an actor in his own fictional world. The story now becomes a 'history' with the author following the antics of his leading characters. They have taken on a fictional life of their own dictated, not by Cervantes but by the manuscript he found. Cervantes is now an investigator trying to comprehend his own creations.

In Book 2 the author transforms into a character. Fiction has taken over the pretended historical realism of the novel. With the introduction of the pirated version theme fact is incorporated into fiction.

This fusion of reality and fiction plays out not only in Quixote's perception and the author's pretence of historical truth but in the reader's mind, too. We wonder why the knight cannot see that he is living a parallel life or the reason for the pretence of the author's false manuscript. These doubts lead to reflect on our own acceptance of fiction. We question our own 'willing suspension of disbelief' and this enables more self-awareness. Readers have followed the same path as Don Quixote and Cervantes: we have become narrators.

Characterisation

The characters in both books are at the centre of story. It is their experience which is under scrutiny so that all other literary effects are subordinated to their perspectives.

Experience brings self-awareness to the characters. One example is Dorothea. She looks like a pastoral painting when she is seen with her feet in the brook. However, when she describes how Ferdinand brought chaos into her life she becomes a thinking feeling character. Through experience she is able to play the role of Princess Micomicona, though still unaware of geography. On the contrary Don Diego de Miranda, the priest and the niece Antonia Quixana remain static figures because their experiences are routine.

The adventures are certainly comic but they are also testing grounds for the characters. The results offer information about their true nature. Virtuous Camilla when tested is shown to be an adept adultress. Sancho us also put to the test on several occasions and remains faithful to his knight. The Duke and the Duchess episodes are a series of tests of Quixote's chivalric values. His ultimate knightly evaluation comes when Carrasco puts a sword to his throat and Quixote prefers to die rather than deny Dulcinea's perfection.

The weather is used by the author to make revelations about the characters. The adventures of Mambrino's helmet stem from a burst of rain which makes him put a basin on his head for protection. The scorching July sun of Castille underlines the craziness of beginning a life of chivalry then.

Topography also adds to the characters' actions. The barren Sierra Morena serves as a suitable background for Quixote's penance, Cardenio's meetings, Dorothea's tale and as a refuge from the police.

Character development is also driven through recurrent themes. Sanchez often insists that his blanketing is deplorable; Quixote is haunted by Dulcinea's disillusion; Altisidora constantly courts the knight; Sancho's dream island is finally his; pastoral life appears and disappears throughout the novel in the guise of the new Arcadians.

The succinct descriptions of adventures maintain the reader's attention yet depict events in epic style. The famous windmill scene is told in less than 50 lines:

"I tell thee they are giants and I am resolved to engage in a dreadful unequal combat against them all.' This said, he clapped spurs to Rosinante . . . . At the same time the wind rising, the great sails began turning . . . . Well covered with his shield, with his lance at rest, he bore down upon the first mill that stood in his way, giving a thrust at the wing which was whirling at such a speed that his lance was broken into bits and both horse and horseman went rolling over the plain, very much battered indeed."

Cervantes places the charcters' self-awareness at the core of the narrative. It is through his reading of chivalric novels that Don Quixote sets out on his adventures. Sancho appears as the pragmatic foil to Quixote's idealism and allows the reader to view his antics from the outside. In the 'historical' part it is Cervantes himself who has become aware that his characters have taken on a life of their own. Their creator becomes their biographer.

In Book 2 Cervantes disappears into the novel as a character leaving the reader to reflect on who is in charge of the tale. Readers are led to recognise that the fiction they are experiencing is a production of their imagination in contact with the narrative. Their insight is that they are narrators. Just as the characters have changed their self-consciousness through the imact of their experience and Cervantes has become aware of the limits of his authorship so, too, readers gradually understands their role as creators in the narrative. We are all characters spinning a tale. As a contemporary of Cervantes wrote:

"All the world's a stage, And all the men and women merely players; they have their exits and their entrances, And one man in his time plays many parts,..." (As you like it by Shakespeare)

Themes

Truth and Falsity

Quixote's distorted perception of reality lies in his belief that romance novels are real. The other people he meets view them as fictions. The protagonist's struggle is to vindicate his own belief by demonstrating that conventional perceptions need refining.

In Don Quixote Cervantes satirises the collective acceptance of truth and presents it as a shared hallucination. The barber perceives his saddle and basin as something different because people around him see them that way. Other characters with stubborn myopic views are included in this satirical send up of communal truth.

Quixote is the incarnation of imaginative truth which depends on each person. For him stories of chivalry are true not because of themselves but because people believe them and so make them true. Fiction needs people's faith to sustain it. Truth for the knight is an aspiration, the world as it should be.

However Quijote himself learns to look beyond private truth and tries to reconcile it with collective truth. He finds that living in his personal truth is painful and sometimes unethical. When he meets a group of actors he tells Sancho that he must look beyond appearances to find truth, that is, collective truth. Finally he fails to synthesise both truths and on his deathbed admits that his chivalric obsession was an error:

"You must congratulate me, my good sirs, because I am no longer Don Quixote de la Mancha but Alonso Quixano, for whom my way of life earned me the nickname of “the Good”. I am now the enemy of Amadis of Gaul and the whole infinite horde or his descendants; now all those profane histories of knight-errantry are odious to me; now I acknowledge my folly and the peril in which I was placed by reading them; now, by God’s mercy, having at long last learned my lesson, I abominate them all."

Literature, Realism, and Idealism

In the first part of Book 1 the main characters Quixote and Sanco appear to be carton cutouts of idealism and realism. They are mirrors of platonic ideals and aristotelian pragmatism. The former holds that the world can be changed through ideas; the latter holds that matter exists independently of human perception. Quixote perceives the world as a set of chivalric beliefs: honour, courage, gallantry...; Sancho sees a world full of sensory realities.

Cervantes applies this philosophical distinction between external and internal visions to literature. Through Quixote the author mocks the failures of realism in romance novels. His own adventures are failures because they are based on the irrealities of chivalric tales. However, characters like the priest who only believe in literary realism are made fun of, too. In his conversations with the innkeeper it becomes apparent that the priest's private perception invades his conception of realism in literature and that objectivity is impossible. Cervantes is suggesting that the world is neither wholly external nor internal but a collection of differing perspectives, indeed different narratives.

The book casts doubt on both personal realism and collective truth and suggests that reality is mixed. This is effected literarily through Quixote and Sancho growing out of their stereotypes through a process of self-awareness and becoming more complex characters.

Sanity and Insanity

Quixote's insanity stems from his distorted perception of realities. Seeing giants instead of windmills is a false interpretation of the objects, just as his obsession with chivalry is an imaginative eccentricity. He does not see what is not there but perceives it through the lens of a knight. The barber and priest who try to rectify Quixote's perceptions are simply against his eccentricities because they are strange. For them his insanity is a threat to their beliefs about reality.

"Too much sanity may be madness — and maddest of all: to see life as it is, and not as it should be!"

Quixotic madness is a trust in imagination over perception because the former is captivated by chivalric legends. However, the knight has the ability to learn from his failed adventures. He gradually gains self-awareness but that leaves him without his coherent imaginative world and what remains is bland reality.

Cervantes himself takes stock of his own imaginary world when he attributes it to a fictional Arab author. In Book 2 he steps further into his story by becoming a character. The story has overtaken the storyteller. The readers are the final piece of this fictional puzzle when they realize that the book's fictional world has taken over part of their imagination and they perceive Don Quixote as a person freed from his creator.

Fiction

Don Quixote is a fiction about fiction. The protagonist lives out his own fiction of being a knight copied from his reading of romances. Cervantes invents his own fictional manuscript translated from the Arabic and in Book 2 enters the fantasy world he created as a character. The reader is gradually made aware that all the entertaining adventures of the knight and the discussions on their make-believe world by the realist Sancho and other characters are actually arguments for and against fiction: which is preferable - the wildly humorous adventures of Quixote or the tame perceptions of the others? Readers come to realise that all are perceptions, narratives, fictions and that that applies to their own thoughts.

The chapters which introduce Ginés de Pasamonte reveal the interest of the author in fiction. He first appears in chapter 22 of Book 1 as a criminal freed by Quixote. He tells his rescuer that he is a writer. This interests Quixote as an avid reader and he asks more about the autobiography:

"So good is it," replied Gines, "that a fig for 'Lazarillo de Tormes,' and all of that kind that have been written, or shall be written compared with it: all I will say about it is that it deals with facts, and facts so neat and diverting that no lies could match them."

"And how is the book entitled?" asked Don Quixote.

"The Life of Ginés de Pasamonte," replied the subject of it.

"And is it finished?" asked Don Quixote.

"How can it be finished," said the other, "when my life is not yet finished?

Facts and fictional lies, life and the fictional reporting of life are so related that the reproduction can only end at death. This is, of course, how Don Quixote's fictional knighthood ended - on his deathbed.

The passing reference to the picaresque novel Lazarillo de Tormes is another Cervantes' wink at his own composition of the adventures of Don Quixote which are portrayed following picaresque fiction.

Ginés appears again in chapter 26 of Book 2, this time as a puppeteer. Quixote once again allows himself to be taken over by his imagination and misinterprets the play as reality. He ruins the puppets but realises his error and apologises for his mistake. The fictional puppet show has enabled the hero to become more self-conscious and distinguish between play acting and reality. The reader also appreciates that a fictional illusion is not life, contrary to what Ginés proclaimed in Book 1.

Other characters act like puppeteers in the book. Altisora pretends to sue for Quixote's love but when her manipulation leads to failure she reacts with vengeance. This is her feedback about who she really is. Dorothea acts the part of Princess Micomicona but is not conscious of how real her performance is. The same as in fiction things are not what they seem in real life either.

In the Montesino cave dreams are the fictional subject. The spoofing begins immediately as the protagonists are led there by an author who resembles Cervantes since he writes parodies of classical works. There follows a quixotic tale of enchanted dreams which Sancho refuses to believe. The final illusion comes, fittingly, at the end of the novel when Quixote wishes his adventures to be forgotten. The same hero now realises that life is a dream and it only ends at the reality of death. In the same way the reader's fictional dream finishes at the same place, the end of the book.

A generation later this ancient platonic theme of life as a dream was composed as theatre by the playwright Calderon de la Barca in his 'Life is a dream' (1635):

"¿What is life? a frenzy

What is life? An illusion,

a shadow, a fiction,

and the greatest good is small:

that all life is a dream,

and dreams are dreams."

No comments:

Post a Comment