Abstract

Context

Traditional moral beliefs and practices were grounded in religion. The Bible and the Quran laid out moral rules that believers thought to be handed down from God. The fact that these rules supposedly came from a divine source of wisdom gave them their authority. They were not simply somebody’s arbitrary opinion, they were God's opinion, and as such, they offered humankind an objectively valid code of conduct.

With the scientific revolution of the 16th and 17th centuries that led to the Enlightenment, these previously accepted religious doctrines were increasingly challenged as an unreasonable faith in a divinity. Organised religion began to decline among the educated elite.

This new way of thinking created a problem for moral philosophers: If religion wasn’t the foundation that gave moral beliefs their validity, what other foundation could there be? If there is no God—and therefore no guarantee of cosmic justice ensuring that the good will be rewarded and the bad will be punished, then why should anyone bother trying to be good? The solution moral philosophers needed to come up with was a secular determination of what morality was and why we should strive to be moral.

One answer to the problem, the Social Contract Theory, was put forward by Thomas Hobbes, John Locke and Jean-Jacques Rousseau, who set out different solutions for a secular morality. Hobbes believed in a strong central authority to prevent the chaos of a "war of all against all." Locke emphasized natural rights and the need for government to protect life, liberty, and property. Rousseau focused on the general will and collective sovereignty, advocating for a society that aligns individual freedom with the common good. These differing formulae for a Social Contract stated that morality was essentially a set of rules that human beings agreed upon amongst themselves in order to make living with one another possible.

Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712-1778) did not have a formal education, though he read widely in philosophy, political science, modern and ancient literature. This led him to mediate in his writings between opposite political theories, such as those of Hobbes, Montesquieu and Locke, in a seemingly contradictory synthesis. In some works the author embraces the conservative views of Grotius and Hobbes who argued for subservience to Absolute monarchs as the only way to avoid falling into the brutality of Nature. However, like Montesquieu and Locke he also sustains it is necessary to support individual rights in order to protect citizens from the abuses of power.

Despite recording these conflicting contemporary approaches, Rousseau was a classicist at heart. He admires Aristotle's Politics and, while applauding direct democracy in Sparta, concludes that it would be impossible in his time. His project was to describe how humans could progress from their natural state to a civil society, while respecting the common good.

On arrival in Paris in 1742 he met Diderot and so was introduced to the thinking of the Lumières who were to author the Encyclopédie. These philosophers had differing ideas but a common belief: human reason was the key to progress. This made them hostile to religious revelation and dogma, received knowledge and blind faith. At first Rousseau maintained a friendship with the Encyclopedists but later they fell out when the author defended religious faith and poured doubt on reason as a means of human progress.

Rousseau's reaction to the formal rule of reason followed by the Enlightenment had its foundation in a new revolutionary romanticism. This was an attempt to find a secular substitute for religion in order to escape the utilitarian and empirical vision of his contemporaries. Egalitarianism, the cult of the common man and his questioning of social hierarchy all form part of his romantic outlook. His abstract reference to a supposed 'state of nature' also has a romantic tinge since it evokes a past state of Eden. In this state human nature was good, but now it has been spoiled by social influences, according to the author. This concept laid the ground for the later Romantic idea of free expression in art, ignoring formal human rules, and a harking back to Nature. His outlook challenged the Enlightenment vision which sought to impose order on the chaos of raw human experience.

Summary

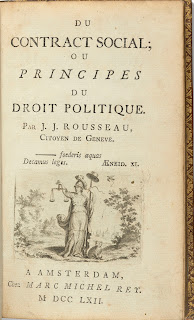

In The Social Contract or Principles of Political Rights (1762) Rousseau tries to articulate how individuals can integrate into the community. Individual liberties are to be guaranteed by an ideal social contract which defines how the common good is the reasonable criterion for this goal of synthesis between the particular and the general. His republican ideal is expressed in four parts: renunciation of natural rights in favour of the State which will protect and bring about equality and liberty; through the legislature the people will safeguard the common good against groups of interests; democracy will remain pure through legislative assemblies; the creation of a State or civil religion.

Rousseau presents his ideas in a four volume book.

The Social Contract opens with the words:

“Men are born free, yet everywhere are in chains.”

He then describes the many ways in which civil society enchains humanity’s birthright of freedom. He complains that the community does not ensure equality and liberty. The author asserts that the only legitimate authority is that which people consent to. Citizens enter into a social contract with the government to ensure mutual protection.

The ideal form of this social contract is formed by all who make up a civil society, which he calls the "sovereign" and which expresses the will of the community. He defines the general will as the need to administer for the common good.

The laws of the State are informed by the general will and, though codified by a lawgiver, should express the general consensus. All laws must maintain equality and individual liberties, though local circumstances may affect particular people in specific conditions. Laws depend on the general will of the people, but an executive body is needed to oversee the enforcement of the law and daily workings of the State.

Government can have different formats: monarchy, aristocracy and democracy. All these forms have advantages and drawbacks. Monarchy is the strongest arrangement and is suitable for hot climates. However, according to Rousseau, rule by the few, aristocracy, is the most stable and most preferable form of government.

The author maintains that to avoid serious conflict between the government and the will of the people the sovereign must convene periodic assemblies where the people vote on the general will. Rousseau believes that in a healthy State assembly votes would be almost unanimous as the people will know and vote for their general interests. This referendum system must include the votes of all citizens, not representatives, since that would mean a loss of sovereignty. The philosopher also proposes the existence of courts as mediators, in case of conflicts between the sovereign and the government or between individuals.

Themes

Freedom

For Rousseau total freedom is the natural state of humanity. He defines this freedom as physical, not being dominated by others or a repressive State, and freedom of spirit, since not enslaved by artificial social needs. According to Rousseau passions lead to needs and desires. In the state of nature needs are limited to survival and reproduction requirements. Modern societies multiply needs to include nonessentials like entertainment and luxuries, which become necessities and enslave us. These are the basis for moral inequality, since some have to work to fulfill others' needs, leading to domination. The author believed that his contemporaries were alienated from their natural freedom and this caused the social ills of exploitation, domination and depression.

His solution to these social diseases was the Social Contract which would ensure individual freedoms along with some constraints. However, Rousseau admitted that property and laws would never allow people to be completely free.

The State of Nature

Rousseau describes the state of nature, a term coined by Hobbes, as the imaginary place and time in which humanity lived in a condition uncorrupted by society. People had total physical freedom, could do as they wanted and were not coerced by the State or society, unlike contemporary times when people accept the law, property and inequality as natural. Nevertheless, the disadvantage was that in the state of nature neither rationality nor morality had yet been discovered.

Rousseau and Hobbes' conceptions differ. The English philosopher envisaged the state of nature as that of war and savagery. Hobbes also viewed human nature as basically brutish. ("Man to Man is an arrant Wolfe"), while Rousseau believed that human nature was essentially good. He admitted, however, that we could never return to the former state of nature and so it was necessary to realise our full natural goodness.

Equality

Rousseau differentiates between two kinds of inequality: natural and moral. Natural inequality comes from age, health or other physical differences and cannot be questioned. Moral inequality stems from human conventions. The author explored the origin of this convention in a thought experiment he called the state of nature.

Human inequality does not exist in the state of nature, except for physical differences. What creates social inequalities, according to the author, is class distinction, and the dominance and exploitation of some over others, resulting from ownership of property. A consequence of property is work and the oppression resulting from it. His main point is that property created inequality between humans. Historically, when our ancestors began to cooperate in agriculture and industry, private property arose and inequalities commenced.

Rousseau argues that institutionlised property is at the root of moral inequality because if people possess things then their patrimony has no relationship with their physical differences. He asserts that all humans are more or less equal in their natural state and identifies ways for a just government to impose equality. This led to a call for a stable government, guided by a contract that would unite many wills into one. However, the author does not denounce property in itself (like the anarchist Bakunin in the next century) but the inequalities caused by property.

The General Will and the Common Good

The will of the sovereign, everyone together, is the general will whose aim is the common good, meaning what is best for the whole State. In a healthy State citizens know what is good for the collectivity, above their own interests. This will take the form of law which will ensure individua freedoms.

Rousseau recognised that the concept of general will was abstract, not specific. It set up rules and systems of government, but did not determine which individuals were accountable to the regulations. Each person who gave up their individual rights to the general will were voluntarily surrendering their personal freedom because they decided the laws.

When, through mutual cooperation, men began to engage in agriculture and industry and to possess private property, inequalities arose and along with them, the need to establish a stable government by means of a contract that unites many wills into one.

Sovereignty

The French tradition of Sovereignity was summarised by Louis XIV's saying, "L'État c'est Moi." In Rousseau's time the monarch was absolute ruler. However, the author gave the word another meaning by saying that sovereignty resided in the people and their general will must not be invalidated by anyone outside their collectivity. The government thus becomes an enforcer of respect of the people's will, not of its own.

However there is a certain absolutism in Rousseau's sovereign. It is as absolute as that of Hobbes, except that the Englishman concentrates power in one person, the King, while the Frenchman focuses it on the General Will. The comparison between the two conceptions has been expressed as: “Rousseau’s sovereign is Hobbes' Leviathan with its head chopped off”.

No comments:

Post a Comment