14th. century Europe was marked by war, famine and the Black Death. Long distance trade increased and feudal society gave way to the power of merchants. The Catholic Church dominated society but it was a corrupt power. This led many towards a more secular worldview.

During the first part of Francesco Petrarca's life (1304 -1374) the European context was conditioned by the Hundred Years War (1337-1453) between England and France and by the move of the papacy to Avignon. The author lived his early life there where his family had moved following Pope Clement V. He studied law in Montpellier and Bologna. He was offered a papal secretaryship in 1347 by Pope Clement VI, but refused it, along with a bishopric.

While on a diplomatic mission in Verona, in 1345 Petrarch discovered the epistles of classical authors, particularly Cicero. It provided a path for him to enter the world of classical thought and a different way to understand himself and his world. He began to seek a reconciliation between the pagan past and Christianity. Despite being a cleric he fathered two children outside marriage. He was deeply interested in education and believed that a new golden age of thought could come about by reviving the ideals of the ancients, against the traditional Church approach, in an educational revolution. This has earned him the name of 'father of Renaissance humanism'.

Petrach, however, had two main limitations: he had no knowledge of Greek and his interest in history stopped at the first century B.C. This meant that he lost out on the cultural influence of ancient Greek thought and was limited in his appreciation of its Roman continuation. Nevertheless, Petrarca set in movement an interest in the classical world which would lead to a renewed enthusiasm for Greco-Roman culture: the Renaissance.

Summary

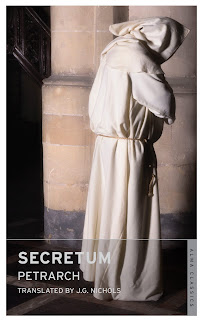

Secretum (De secreto conflictu curarum mearum) is a trilogy of dialogues in Latin written by Petrarch between 1347 and 1353. It is an examination of the Catholic faith through an imagined dialogue with Augustine of Hippo's teachings, accompanied by Truth. He emphasises that it is possible to mix secular achievements and a relationship with God, arguing that human creativity should be used to its fullest.

In Book one the discussion centres on whether someone can be unhappy against his will. The replies draw on a number of Stoic beliefs, Cicero's Tusculanae disputiones and Augustine’s De vera religione. In this first dialogue Augustine insists that Petrarch's priority of this life over the afterlife is the root of his unhappiness. He advises that he knows what the problem is: Petrarca should think more about death. According to Petrarch's interlocutor mortality should be the focus of human thought. Life comes to an end. And then? The answer is that mortal life is the precursor of the hereafter, so life should focus on that. Petrarca admits to not understanding thus conception of living.

So Augustine summarises his perception:

"If whenever you think of death you are not disturbed, you will know that your thoughts have been useless, as if you had been thinking of something else."

In Book two Augustine examines Petrarch on all seven deadly sins, starting with pride. Petrarca admits his spiritual shortcomings, particularly his desire for fame which is the reason of his writings. As Augustine comments:

"I must say with all due respect that you have gone seriously astray by exhausting yourself in the effort to write books, particularly at your age."

Petrarch's concern with mortality has a secular format: fame in posterity. He is much less concerned with his soul's immortality.

Book three sees Augustine accusing Petrarch of not seeking salvation because he is held back by love and glory. These are the same fetters which held Augustine before his conversion. Glory is recognition and the love theme is his obsession with Laura.

In the latter part of Book 3 Augustine challenges Petrarch's literary celebration of Rome in De viris illustribus and the epic Africa. The criticism is that by dedicating his efforts to these scholarly works Petrarch has substituted the goal of saving his soul for that of achieving literary fame and glory.

The author occasionally falls into a comic exaggeration of augustininan thought:

"The safest thing is to scorn oneself; scorning others is extremely dangerous and vain. But let's move on."

Petrarch's does admit a sensory based optic on life which perhaps prevents him thinking more transcendentally:

"I deeply regret not having been born indifferent to the senses. I would prefer to be some inert stone than to be tormented by so many stirrings of the flesh."

In fact Augustine is so far from his own viewpoint that he admits, comically:

"I've already been thinking of running away, but I'm not quite sure which way is best to go."

Themes

The Dark Ages

It is generally accepted that the term "Dark Ages" was invented by Petrarch in the 1330s. He borrowed the common Christian metaphor of darkness/light to signify evil/good. However, he chose to reverse its application and give it a secular meaning. He renamed Classical Antiquity the age of light because of its cultural influence and called his own time the age of darkness.

His aim was to restore classical Latin to the pure state it had before the Vulgar Latin of the Romance languages. Renaissance humanists saw the previous 900 years as stagnation and rejected Augustine's religious view of the Six Ages of the World (Adam to Noah, Noah to Abraham, Abraham to David, David to the Babylonian exile, the return to the Christian era). However, humanism preferred a secular outline through the evolution of Classical ideals, literature, and art. For Petrarch there were two historical periods: the Classical Greco-Roman one, followed by a time of darkness, which included his own age:

"My fate is to live among varied and confusing storms. But for you perhaps, if as I hope and wish you will live long after me, there will follow a better age. This sleep of forgetfulness will not last forever. When the darkness has been dispersed, our descendants can come again in the former pure radiance."

Humanism

Petrarca spent much of his free time searching for lost works of classical authors. In the library of Verona cathedral he found a collection of Cicero's letters, Epistolae ad Atticum, in 1345. He copied the manuscript and circulated it among his friends. By the 15th. century Cicero's tense, philosophical style had become the standard for Latin prose.

Petrarca began to recognise the gap between his own times and those of Cicero. He distanced himself from the contemporary religious vision of classical texts as testimonies to ruined times, and underlined the values held by the ancients. Petrarca advised reading Roman authors as models for eloquent expression and ethical behaviour. He presented ancient Rome as a golden age of moral values and great deeds. He coined the term "medio evo” (middle ages) to describe the decline in Roman values, arts and literature and encouraged the rinascita (rebirth) of classical learning in his own age.

To emphasise his point of view Petrarch exaggerated the cultural decline in the Middle Ages which, in fact, had built huge gothic cathedrals, innovated trade links and generated science and theology. He classified the times after the demise of the Western Roman Empire as dark and ignorant, which left us a distorted picture of that Age.

The revival of interest in Roman antiquity promoted by Petrarch moved many 15th. century humanists to search libraries where they found more of Cicero's letters and many other texts, among them Lucretius’s Epicurean poem, De Rerum Natura (On the Nature of Things). Greek scholars escaping from the 15th. century Ottoman attacks on the Eastern Roman Empire brought Homer, Plato, Sophocles, and other Greek manuscripts to Italy. They also taught Greek to a generation of humanists and so opened up the ancient Greek writings to the West.

Humanists displayed a keen interest in education. Their educational programme, studia humanitatis, was devised in opposition to the Middle Ages scholastic tradition of logic and theology. Their aim was secular, not to make theologians but citizens useful to government and society. The curricula consisted of five subjects: grammar, rhetoric, poetry, moral philosophy, and history. The aim was to develop the social values of ancient Greco-Roman societies, the uomo universale, helping students to realize their potential as individuals, know the moral good and act on it.

Language

Petrarca believed that ancient Latin should be revived as the literary, moral and religious language of the cultural reform of his times. This was envisaged as a return to virtue and moral living. In apparent contradiction the author thought that this return to Christian ethics could be effected through imitating the ancient Roman writers who were pagans. Many humanists concentrated on literary style but Pertrach's humanism retained a Christian focus, often emphasising piety and devotion over classical learning and eloquence:

"If admiring Cicero is being a Ciceronian, then I am a Ciceronian. For certainly, I admire him, and I marvel at others who do not admire him. If this seems to be a new confession of my ignorance, I confess that it reflects my feelings and my wonder. But when it comes to pondering or discussing religion – that is, the highest truth, true happiness, and eternal salvation – then I am certainly neither a Ciceronian nor a Platonist, but a Christian."

Petrach's goal was a synthesis of moral philosophy and eloquence, where skill with words would motivate people towards virtuous living. His model was Augustine of Hippo, who had redefined classical philosophy in Christian terms. Petrarch's criticism was directed less at scholastic language and more at the anti-christian tendencies in Aristotle and Averroës. In particular he rejected the concepts of the soul's preexistence and the eternity of the world. He also saw aristotelian moral philosophy as too abstract for enabling practical improvement in moral living:

"For it is one thing to know, and another to love; one thing to understand, and another to will. I don’t deny that he teaches us the nature of virtue. But reading him offers us none of these exhortations, or only a very few, that goad and inflame our minds to love virtue and hate vice."

Petrarca attacks the contemporary scholastic teaching with invective, but he does not analyse its language closely, as other humanists did. His underlying thesis seems to be the close relationship between style and thought. His fundamental critique is that confused thinking leads to poor morals. His goal is to use the clarity of classical Latin to encourage clear thinking and so ethical behaviour: clarity of thought to ensure moral action.

No comments:

Post a Comment